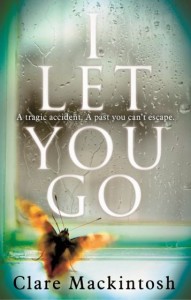

One of the first blogs I read and connected with was written by my online friend Clare Mackintosh. That blog has long since vanished but Clare has since gone on to become a Richard and Judy Book Club best selling author with her debut novel I Let You Go. I’ve included an extract from the book at the end of this blog and if you enjoy that I urge you to get hold of a copy.

One of the first blogs I read and connected with was written by my online friend Clare Mackintosh. That blog has long since vanished but Clare has since gone on to become a Richard and Judy Book Club best selling author with her debut novel I Let You Go. I’ve included an extract from the book at the end of this blog and if you enjoy that I urge you to get hold of a copy.

Clare is a really inspirational woman having succeeded in a career change whilst managing three small children and a literary festival. Over the past year when I’ve been trying to set up my own literary festival Clare has been a godsend and I don’t think we could have managed to run it without her advice! I’m thrilled to welcome her here on my blog to talk about writing and parenting as part of the blog tour to celebrate the book:

Writing and parenting

‘There is no more sombre enemy of good art,’ said Cyril Connolly, ‘than the pram in the hall.’ In other words: have children, and you can forget that dream you had of becoming a writer, a sculptor, a musician. You’ll be forever sleep-deprived, creatively stifled, and at the beck and call of an army of pygmy warriors.

There’s an element of truth in that: sleeplessness can certainly be an enemy to creativity, but it can also stimulate it. I remember feeding my twin girls in the dead of night; the house quiet and dark, and only the ticking of the clock stopping me from feeling that time had stood still. At the time I was deeply, terrifyingly in the throes of post-natal depression, swamped by irrational fears and unable to see a way out. I didn’t know it then, but the emotions I was experiencing would become the basis for a book.

One has only to look at the rise of what is sometimes referred to as ‘domestic noir’ to see how fascinated readers are by the darkness present in people’s every day lives, and it is perhaps not surprising that so many thrillers and crime novels centre around families. The home is where we feel safe: our children are the people we care most about in the whole world. Put one – or both – of those things in jeopardy and you’ve got a novel!

From the writers perspective it is no harder to juggle parenting and writing than it is to combine being a parent with any other job, and in a great many cases it is significantly easier. I went back full time to my job as a police inspector when my children were 3, 2 and 2. Day to day it just about worked, but I never saw my family, and I constantly felt stressed that I was going to drop the ball. Now I write whenever I have time. The children are all in school, so I have all day to play with, and I can be there for every drop-off and pick-up, and for every harvest festival, Nativity performance or parents’ evening. Sick children take up residence in my office on a pile of squashy cushions, and doze or read until whatever bug has left them. In the holidays I work in the evenings, or get up early to write before they’re properly awake. It’s tiring, but it’s a small price to pay for being with them as they grow up. I am acutely conscious of how fast time is going, and after such a rocky start with the girls, I am grateful I don’t need to miss out on any of it.

I write psychological suspense novels with a strong emotional pull, and I doubt I would be writing at all, had it not been for my children. The emotions I experienced as I went through fertility treatment; became pregnant with twins; gave birth prematurely; held my son as he died; became pregnant with twins again… all these experiences gave my writing a richness and a depth I couldn’t have replicated with a different life. More prosaically, when I decided I was missing out as a parent, and wanted to quit my career in the police, it was the children who drove me forward – not to mention providing me with material! I wrote for parenting magazines and websites, used them shamelessly in articles and columns, all with the aim of earning enough money to keep the wolf from the door. The pram in my hall is more of a friend than an enemy, and I wouldn’t have it any other way.

Extract from I Let You Go

When I wake, for a second I’m not sure what this feeling is. Everything is the same, and yet everything has changed. Then, before I have even opened my eyes, there is a rush of noise in my head, like an underground train. And there it is: playing out in Technicolor scenes I can’t pause or mute. I press the heels of my palms into my temples as though I can make the images subside through brute force alone, but still they come, thick and fast, as if without them I might forget.

On my bedside cabinet is the brass alarm clock Eve gave me when I went to university – ‘Because you’ll never get to lectures, otherwise’ – and I’m shocked to see it’s ten-thirty already. The pain in my hand has been overshadowed by a headache that blinds me if I move my head too fast, and as I peel myself from the bed every muscle aches.

I pull on yesterday’s clothes and go into the garden without stopping to make a coffee, even though my mouth is so dry it’s an effort to swallow. I can’t find my shoes, and the frost stings my feet as I make my way across the grass. The garden isn’t large, but winter is on its way, and by the time I reach the other side I can’t feel my toes.

The garden studio has been my sanctuary for the last five years. Little more than a shed to the casual observer, it is where I come to think, to work, and to escape. The wooden floor is stained from the lumps of clay that drop from my wheel, firmly placed in the centre of the room, where I can move around it and stand back to view my work with a critical eye. Three sides of the shed are lined with shelves on which I place my sculptures, in an ordered chaos only I could understand. Works in progress, here; fired but not painted, here; waiting to go to customers, here. Hundreds of separate pieces, yet if I shut my eyes, I can still feel the shape of each one beneath my fingers, the wetness of the clay on my palms.

I take the key from its hiding place under the window ledge and open the door. It’s worse than I thought. The floor lies unseen beneath a carpet of broken clay; rounded halves of pots ending abruptly in angry jagged peaks. The wooden shelves are all empty, my desk swept clear of work, and the tiny figurines on the window ledge are unrecognisable, crushed into shards that glisten in the sunlight.

By the door lies a small statuette of a woman. I made her last year, as part of a series of figures I produced for a shop in Clifton. I had wanted to produce something real, something as far from perfection as it was possible to get, and yet for it still to be beautiful. I made ten women, each with their own distinctive curves, their own bumps and scars and imperfections. I based them on my mother; my sister; girls I taught at pottery class; women I saw walking in the park. This one is me. Loosely, and not so anyone would recognise, but nevertheless me. Chest a little too flat; hips a little too narrow; feet a little too big. A tangle of hair twisted into a knot at the base of the neck. I bend down and pick her up. I had thought her intact, but as I touch her the clay moves beneath my hands, and I’m left with two broken pieces. I look at them, then I hurl them with all my strength towards the wall, where they shatter into tiny pieces that shower down on to my desk.

I take a deep breath and let it slowly out.

You can find out more about this book, Clare’s forthcoming novels and lots more information over on her website here. You can also find her over on Twitter: @claremackint0sh

No Comments